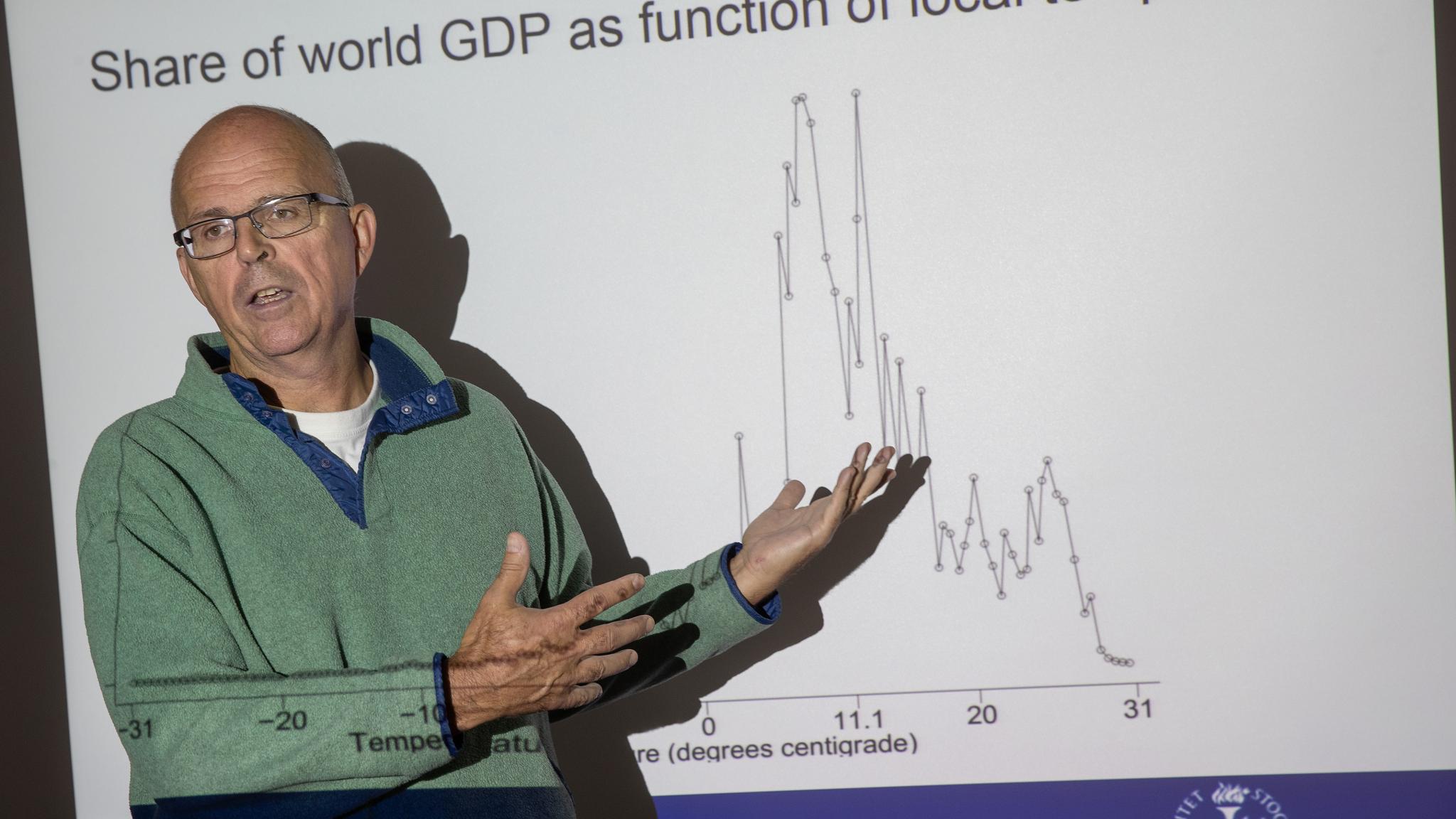

Climate change affects different regions differently

Climate change is a global phenomenon but its impacts are quite heterogeneous across regions of the world. For some regions the changes may entail an economic upswing, while others will experience human, natural, and economic disasters.

Per Krusell

Professor of economics

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Stockholm University

Research field:

Economic effects of climate change

Per Krusell, professor of economics at the Institute of International Economic Studies, Stockholm University, analyzes the interplay between economics and climate change. His main goal is to build a large-scale computational model to show how economics affects the climate, through emissions, but at the same time how temperature changes will affect the development of countries and regions. The model will serve as a tool for evaluating different kinds of policy to combat climate change.

This is an area where the market doesn’t work. Political instruments such as taxes or other political decisions are necessary,” says Per Krusell.

Concrete scenarios

Today it is generally accepted, at least among climate scientists, that emissions from fossil fuels are raising the mean temperature of the earth and have climate-changing effects. But the differential impacts across regions are far less studied. An understanding of these differential impacts can be critical in climate-change negotiations.

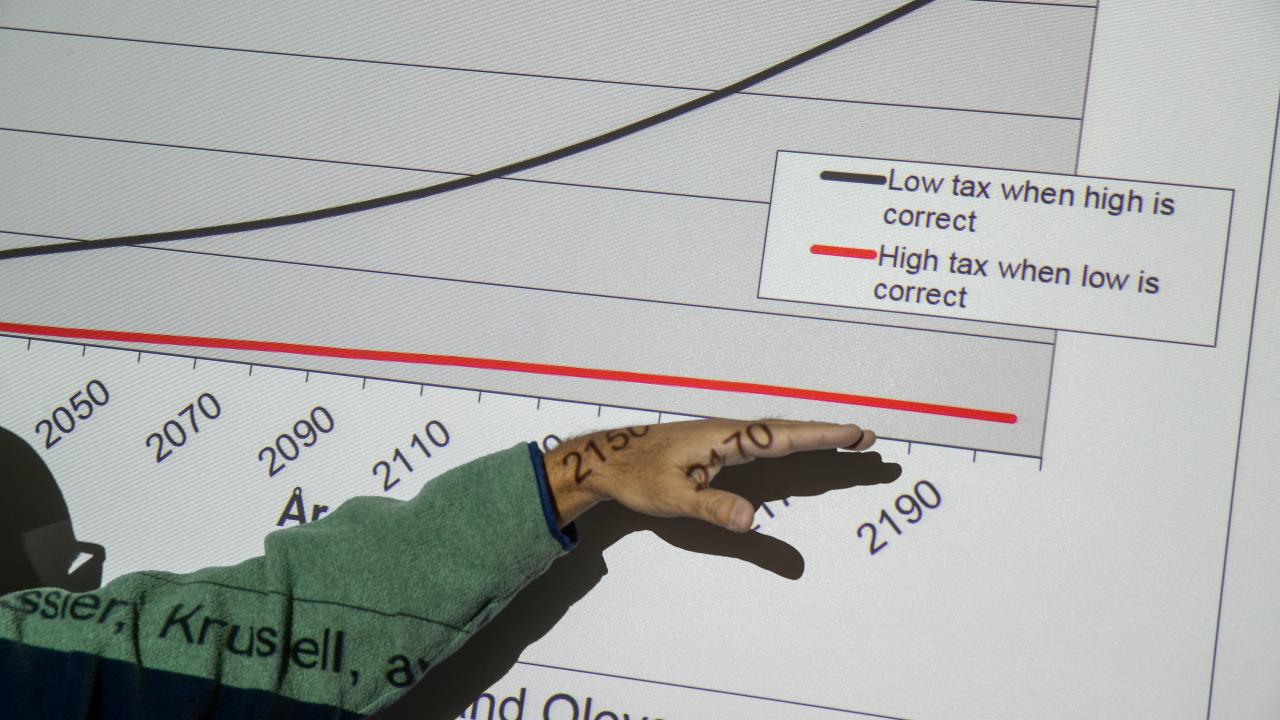

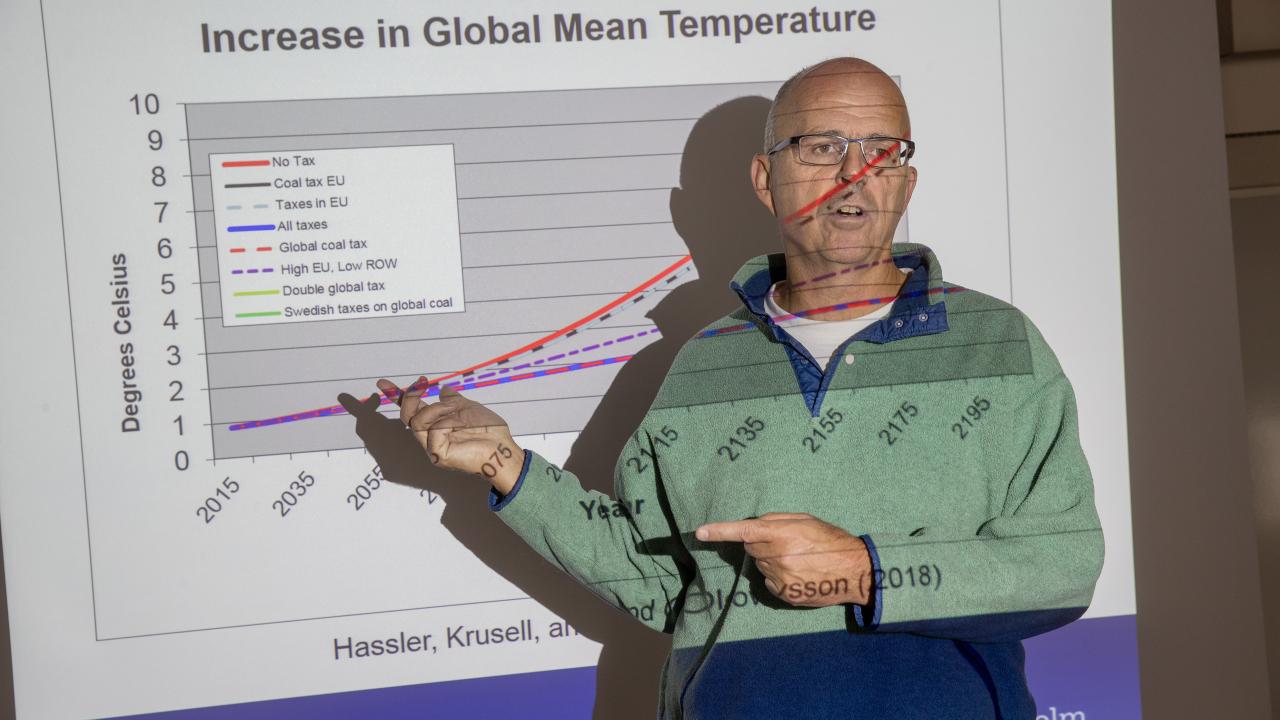

“We use scientific data on how the climate operates in different regions of the world as an input into our model, along with economic data. The model can then be simulated for different scenarios regarding policy. For instance, we can trace out the effects of carbon taxes, also when some countries, like Sweden, are using high taxes whereas others are not,” explains Per Krusell.

There is hope that the model will be powerful for communicating with political decision makers, but also for illustrating the central mechanisms among the general public.

“We’re joining together, into an integrated model framework, solid evidence from both climate science and economics, and we then work out implications for how the climate and the economy interact. There are speculations and claims about what kinds of policies are desirable, but most of these are really unfounded, or at least not derived in a coherent way using frontier scientific knowledge. We hope that our model can be used to show and explain which measures work and which ones don’t,” says Krusell.

“It is important as a signal, a recognition. The funding means that I can recruit internationally, bolster our research competence, and get excellent people to work on the project.”

US and China will get by

Like in all economic models, some normative assumptions are used so that “welfare” can be evaluated in a clear and quantitative manner. Then various negative (and sometimes positive) climate effects are analyzed from the point of view of this welfare criterion.

In the construction of the model, Per is collaborating with researchers from various disciplinary domains.

“We are a network of everything from computer scientists, meteorologists, and natural scientists, to economists, all with the same goal. It’s an unusual way to work for me as a social scientist. What I know about is the economic interactions. I’ve worked with similar model simulations in the past, but then in very different contexts. I didn’t know much about the climate issue before 2006. I was aware of a variety of empirical economic studies measuring climate impacts on a microeconomic level, but I had to invest a lot of time into acquainting myself with the theoretical mechanisms from the natural sciences. In this process, the natural scientists in our group have been very helpful.”

Of course, the model simulations will not deliver exact answers. Per gives an example of the difficulty.

“The area where we know the least is damage assessment. Calculating the losses from something concrete like a flood is possible, but how do you calculate the value of loss in biodiversity?”

The studies so far indicate that areas that are colder today will be more favorably affected than will warmer climates. It will be easier to cultivate land there, and the areas will be more attractive in many other ways. Meanwhile, in warmer areas there may be shortages of food and water, which can lead to higher mortality rates and a greater susceptibility to natural disasters. Two of the world’s great powers, the US and China, on the other hand, seem to be able to get by without being significantly impacted.

“I hope that there will be much more economic research toward improving the measurement of damages and of how warming affects our lives. There are also economic effects of climate policy, and these also need to be better understood,” says Krusell. “Carbon dioxide taxes in certain regions may prompt industries move to areas without taxes, generating rising unemployment.”

Knowledge must reach out to others

Per, who returned to Sweden in 2008 after more than 20 years in the US, is impressed with Swedish authorities and politicians.

“They’re quite good at making use of new knowledge.”

But it is not just a matter of the knowledge of politicians and other decision-makers but also of what ordinary people, voters and consumers, think.

Per Krusell mentions a meeting with the US secretary of energy, a Nobel laureate in physics, where Sweden’s high carbon dioxide taxes were discussed.

“He maintained that the US should have similar taxes but that this is impossible to implement, since people are against it,” says Krusell.

Per Krusell feels that communicative skills will be an important aspect toward the end of the research project.

“Everyone stands to gain from sharing the knowledge that social and natural scientists generate,” says Per Krusell.

Text Carina Dahlberg

Translation Donald S. MacQueen

Photo Magnus Bergström