The health problems of corruption

“The problem of hell”. These are the words Bo Rothstein uses to describe surprising research findings: there is no correlation between how democratic a country is and the level of well-being there. The fact is that people living under a dictatorship in China are doing better than those in India, a democracy. Human welfare depends instead on something else completely: the absence of corruption and equality before the law.

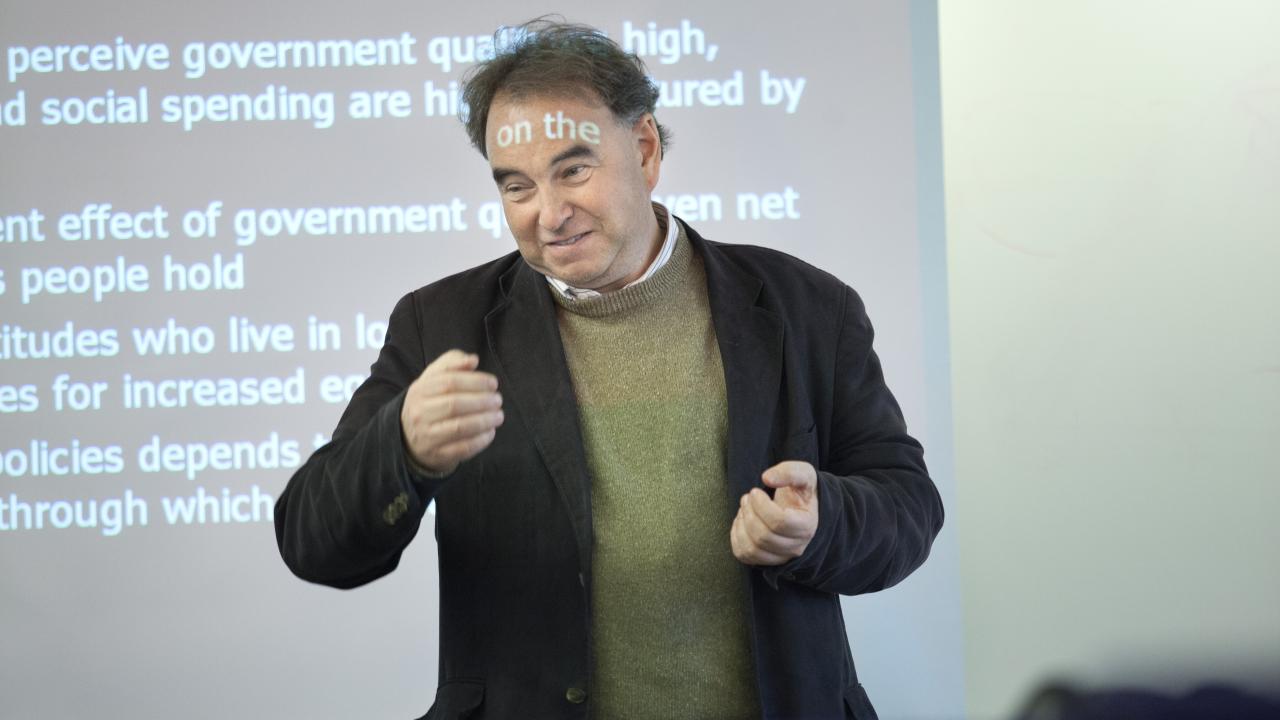

Bo Rothstein

August Röhss Professorship in Political Science

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Research field:

Political institutions’ quality, welfare policy, social reliance, corruption, war on poverty, labor market policy and interest groups.

“The problem of hell”. These are the words Bo Rothstein uses to describe surprising research findings: there is no correlation between how democratic a country is and the level of well-being there. The fact is that people living under a dictatorship in China are doing better than those in India, a democracy. Human welfare depends instead on something else completely: the absence of corruption and equality before the law.

How should a country be governed so that its citizens are as happy as possible?

This is the question being addressed by Rothstein, who is Professor of Political Science at University of Gothenburg. Just over ten years ago he was involved in founding a research institution called “The Quality of Government”. Since then the institution has established a gigantic database, now one of the most frequently used in the world, for this type of social scientific research.

The database includes tens of thousands of interviews with randomly selected inhabitants of most countries in the world. Over one thousand experts have given their view of public sector activities, and the researchers have also entered information capable of measuring welfare: everything from infant mortality rates, availability of water, and the proportion of 12-year-olds who can read, to how satisfied the country’s inhabitants are with their lives.

Based on all these data, the institution’s researchers are now attempting to understand the correlations between human health and national governance.

“We are addressing three issues. In purely conceptual terms, how should we understand what is encompassed by the term ‘quality’ in the public sector? What effects does it have on human welfare? And how can we explain the variations between countries?” comments Professor Rothstein.

Impartial and corruption-free

Professor Rothstein has devoted much time to the first question – the nature of quality in the public sector. The definition must be universal and simple. His conclusion: quality is when public institutions are impartial and free of corruption. Everyone must be equal before the law.

“The task of public employees is to implement and apply national laws and regulations without being influenced by bribes, religious beliefs, gender, ethnicity, family ties, political views or other irrelevant considerations,” Rothstein explains.

Democracy – no guarantee of welfare

Rothstein’s research shows that the degree of corruption in public administration plays a key role in the welfare of the country’s citizens. Surprisingly enough, the extent to which a country is democratic is much less important.

“I would be the last person to argue against democracy. But our depressing conclusion is that it is hard to find a correlation between the degree of democracy and human welfare,” Rothstein comments.

As an example, he compares China and India:

“China is now ahead of India on every conceivable metric for human welfare.”

Countries high up on the list of those with impartial public authorities are: the Nordic countries, countries in north-western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Singapore and Hong King.

But corruption is rife in democracies such as Greece and Italy. Therein lie the roots of euro crisis according to Professor Rothstein:

“Greece and Italy score lower than a handful of African countries in our studies.”

Less corruption with qualified public employees

If corruption impacts welfare in a country – what, then, governs the degree of corruption? Here, the institution has found three interesting angles.

“There is a strong correlation between broad educational reforms and low corruption. The average number of children attending school in 1870 is strongly correlated to current levels of corruption,” says Rothstein.

So education is important. But so is gender equality. The institution’s research shows that the more women in a country’s governing bodies, the less corruption.

Finally, not least important is recruitment of public employees. In countries where appointments are based on merit, corruption is low. In societies dominated by nepotism, there is a greater risk that the authorities will treat people differently.

“Recruitment strictly on merit sends an important signal about the state’s intentions,” comments Professor Rothstein.

It does not help raise the wages of public employees, however. It is a myth that it is hard to bribe a well-paid public employee.

Wrong basis for the fight against corruption

Corruption is waning in some countries. Efforts have been successful in South Korea, Chile, Taiwan and Botswana, for example. But in many other countries corruption is actually getting worse. Professor Rothstein believes that action programs have been based on erroneous theories.

“They have misunderstood the fundamental nature of the problem,” he says.

One predominant belief is that people working in a corrupt public administration do not understand that they are acting immorally. But the institution’s research shows that people in corrupt countries are very well aware that what they are doing is wrong. Another view is that those found to have acted dishonestly should be punished more severely. But this presupposes impartial courts of law, which are precisely what is lacking in corrupt countries.

According to Professor Rothstein, what is needed instead can be likened to a “Big Bang” – a change in public administration so radical that citizens realize that new rules apply. And that those rules apply to everyone.

How and why such radical changes occur remains to be ascertained. The next stage in the research will be to review the history of various countries, and identify key events that have put the country on a path away from corruption and have improved its welfare.

Text Ann Fernholm

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström